Few allocate time towards the so important leading indicators. The variant view is generally built on them: changes in the team, a new executive that brings a new framing to the asset (a.k.a. strategy), a new incentive design in-place, execution capability.

Never Commit

In Amazon’s 2016 letter to shareholders, Bezzos introduced some tenets the company lives by. The one that struck me was “Disagree & Commit”:

Third, use the phrase “disagree and commit.” This phrase will save a lot of time. If you have conviction on a particular direction even though there’s no consensus, it’s helpful to say, “Look, I know we disagree on this but will you gamble with me on it? Disagree and commit?” By the time you’re at this point, no one can know the answer for sure, and you’ll probably get a quick yes. – Jeff Bezzos

The principle seems to work great in the company – and I am certain they’re not the only one to execute this – and seems to fit the “real economy” execution challenge. As Taleb have put it in many different ways and forums, modularity and trial & error modus operandi leads to innovation without compromising the status quo.

Well, I believe the “Disagree & Commit” modus operandi serves investors well, but via negativa. What I mean by that is: investors must disagree with the price of a stock when they either buy or sell it through story-telling, i.e., creating an investment hypothesis that should yield a different price for that security.

But what about committing? I’d like to share two angles:

- Derivative 1: Commit: when you actually buy / sell the security;

- Derivative 2: NEVER Commit. And that’s what I’d like to talk about.

My underlying assumption is that you should never really commit to an investment hypothesis because:

- by design, each security price tells a different version of the future story;

- different pieces of evidence can fit more than one hypothesis. Looking for satisficing hypothesis (MVP) is too narrow, leaving aside many plausible versions (open flanks) of the story in question (imagination & creativity are required);

- What has real value is finding pieces of evidence that falsifies linchpin premises, not the other way around;

- as working hypotheses might change along the way, you should never marry them;

We can intervene through greater understanding of what we can and cannot control, by knowing where potential deceptions lurk, and by a willingness to accept that our knowledge of the world around us is limited by fundamental conflicts in how our minds work. Certainty is not biologically possible. – Robert Burton

This is a risk-based approach to investment philosophy. It corroborates Buffett’s #1 rule of managing money, which is “Never lose money.” It corroborates other investors looking for similarities among different investment philosophies that found the one thing successful investors have in common is the ability to manage risk. It corroborates the need to allocate scarce resources well, in this case, our agendas. Without a strong defense, scoring is just dissipated energy.

The skeptical have a biological/behavioral advantage in managing money. But I have gathered some “Never-Commit” tricks:

- causality is generally hard to be delineated in complex problems. Instead, emphasize procedures that expose and elaborate alternative points of view;

- design a process that clearly delineates their assumptions and chains of inference and that specify the degree and source of uncertainty involved;

- periodically re-examine companies from the ground-up, maybe getting another person to look into it;

- analytical conclusions should always be regarded as tentative. The situation may change, or it may remain unchanged while you receive new information that alters your initial appraisal;

In other words, commit without committing. My holding period is forever; until my appraisal changes.

Doubt is not a pleasant state, but certainty is a ridiculous one. – Voltaire

² Amazon 2016 Letter to Shareholders

Meta-skills: Searching For Leading Indicators Of Nobel-like Performance

Dealing with a set of complex, dynamic, holistic, ambiguous problems seems like a daunting task. Many frame those as intellectually challenging puzzles, but many times they are simply unsolvable mysteries. Too many variables, too many difficult-to-ponder knowns and unkown unknowns. And yet sometimes there’s no other option but to go ahead. Enter meta-skills.

Meta-skills are simply skills that enable one to develop new skills. In other words, they comprise the most basic skill-set one can have. They are the leading indicators of future performance. While causation may confound many, reverse engineering for root causes reduces complex problems into simpler ones. For example, a helpful meta-skill is abstraction, which frequently makes things simple. The capacity to transport abstractions (or ‘mental models’) from field to field is a superpower.

Inspired by the speech of Richard Hamming from Bell Labs, I listed below some meta-skills that may lead to “Nobel-like performance”. Each one of the could be entire posts, but I do not intend to expend such an effort at this moment. Anyway, I understand expliciting those already adds value as time is our scarcest resource and the quick drop-list below already provides a “cheat sheet” for identifying pockets of potential outstanding performance, be it for HR processes or identifying great people at prospective investment companies.

- Intelligently Applied Drive: commitment to be the best, mastery, preparation, repetition, effort

“Don’t settle for less.”

“Knowledge and productivity are like compound interest.”

- Self-Management: time allocation, empathy, self-awareness, capacity to put up with stress, surround yourself with the best, curiosity (seek new challenges)

“If you don’t know what’s important, it’s unlikely you will do outstanding work.”

- Problem solving skills: critical thinking, creativity, imagination, abstraction, prospection and retrospection, capacity to deal with ambiguity, capacity to frame the problem from different points of view;

Why, what’s the evidence? What could make it change? Ponder nuances, think the problem through.

“It ain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it.”

- Communication skills: written & verbal, capacity to summarize and ponder the key variables of a problem-set;

“You can have brilliant ideas, but if you can’t get them across, your ideas won’t get anywhere.”

- Independence: courage to be a thought leader, boldness;

“The real question is whether you dare to do the things that are necessary in order to be great. Are you willing to be different, and are you willing to bear the inescapable risk of being wrong? In order to have a chance of great results, you have to be open to being both.”

- Execution: test your ideas. Make. Do. Create. Implement;

“If you want to do something, don’t ask, do it. Don’t give people a chance to tell you ‘no’.”

“I have been impressed with the urgency of doing. Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Being willing is not enough; we must do.” -Leonardo da Vinci

Deep Research versus Deep Pondering

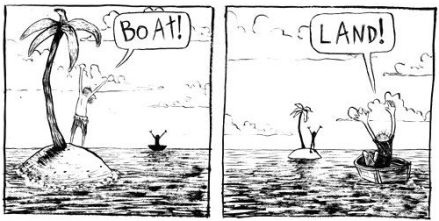

Put bluntly, facts don’t exist. Versions of them do: what is a fact for me, is a picture of a worldy experience that commonly more than one person enjoys. That means that the interpretation of experiences yields different pseudo-facts depending on the points of view.

Even if we could agree on facts¹, different versions of facts exist for each individual. And that’s a big reason many of us like to simplify this disparate view into numbers/financial statements, albeit losing perspective and nuance – still we strive to acknowledge it.

Which begs the question: what is the real competitive advantage in investing? Deep research or deep pondering?

The vast majority of research pieces has the same underlying data and sources, so what would differ among them? Is it a matter of BRUTE FORCE & EFFORT? I’d say deep research is simply a pre-requisite for playing the real game. But what we call “edge” or “variant view” arguably lies within FRAMING, PONDERING, and how you INTERWINE separate pseudo-facts.

The market is a weighing machine (many claim it’s efficient, sovereign and omniscient), but so should we be weighing machines. In the world of big data, robots may arbitrage headlines, but they can’t (at least yet) ponder multiple subjective arguments like we can do. Counterintuitively, stretching investment horizons simplifies our job is in spite of additional possible outcomes. At least we are an order of magnitude right instead of precisely wrong.

¹ Taxonomy and vocabulary certainly are topics to be explored in a future post

Psychology of Intelligence Analysis Annotated: Biases

We are always on a journey to better design our job. This has been my mood during this current Brazilian crisis. I (almost) always come down to qualitative key issues that deter me from further exploring investment ideas, many of those related to people and incentives. The Brazilian Government is no exception. Brazil is a company with a critical governance problem. But I am not that into politics, so let the media, politicians, consultants and lobbyists do their jobs.

However, today I wanted to discuss the last topic of the book Psychology of Intelligence Analysis by Richard Heuer, namely biases. I consider it to be an interesting subject as its definition per se is already curious. If anyone has a bias, it’s because neutrality occurs somewhere, somehow. But, by definition, there is no “neutral” behavior and that’s why I find it ingenious. And that’s what Lee Ross, a psychologist at Stanford University calls “naive realism”, meaning we see the world as it truly is, without bias or error.

Anyhow, the best debate on the topic I have stumbled so far is the classic Charlie Munger’s lecture entitled the Psychology of Human Misjudgement, that I strive to read yearly. As the time goes by, it gets easier to grasp thoughtful concepts and internalize those. If you prefer to listen rather than to read, you can find the full lecture right below.

In Heuer’s book, however, there’s a list of interesting behaviors the CIA have apprehended along the way; simple little tricks cleaning up the path to clearer thinking:

Biases

- Specifying in advance what would cause you to change your mind will also make it more difficult for you to rationalize such developments if they occur, as not really requiring any modification of your judgment

- Statistical data, in particular, lack the rich and concrete detail to evoke vivid images, and they are often overlooked, ignored or minimized

- Consistency can also be deceptive

- People save residual non-accurate information even after being told they are inaccurate

- Be cautious with causation. Remember variance and/or randomness exist

- The tendency to reason according to similarity of cause and effect is frequently found in conjunction with the bias toward inferring centralized direction. Together, they explain the persuasiveness of conspiracy theories

- People have better intuitive understanding of odds than of percentages

- Base-rate fallacy: numerical data are ignored unless they illuminate causality

- People tend to underestimate both how much they learn from new information and the extent to which new information permits them to make correct judgments with greater confidence

- Fighting hindsight: if it was the opposite, would I be surprised based on the previous report?

- Consciously avoid any prior judgment as a starting point

- The act of constructing a detailed scenario for a possible future event makes that event more readily imaginable and, therefore, increases its perceived probability

- Expectations or theory are unlikely to be given great weight and tend to be dismissed and unreliable, erroneous, unrepresentative, or the product of contaminating third variable influences

Psychology of Intelligence Analysis Annotated: Linchpin Assumptions

This is the fourth of a series of posts that I try to lay down the most relevant lessons from the book Psychology of Intelligence Analysis by Richard Heuer.

In my opinion, the next topic lies at the core of investment cases. And it is not the investment thesis per se, it’s a subset of it. Linchpin assumptions are the core companies value drivers. Those are the KPIs executives and investors should understand and follow closely. For investors, those KPIs are simply lagging indicators. For executives, they work with both leading and lagging indicators. Internally, middle management need to act on leading KPIs that shall yield the desired outcome for investors and global goals for the company executives (lagging indicators).

For instance, take a retailer. Gross margin is the lagging indicator. The leading indicator could be the amount of sales sold with some markdown. And the leading indicator of the leading indicator could be a new COO that would redesign the supply chain or even more basic store processes. Many analysts consider gross margin to be the value driver. To be right before Mr. Market, you have to decipher that the COO is the value driver.

Linchpin Assumptions

- “Analysts actually use much less of the available information than they think they do.”

- “People’s mental models are simpler than they think, and the analyst is typically unaware not only of which variables should have the greatest influence, but also which variables actually are having the greatest influence.”

- “When analysis turns out to be wrong, it is often because of key assumptions that went unchallenged and proved invalid.”

It’s easy to become lost with too many pieces of information. One must be sharp, separating what matters from a fundamental value perspective which will eventually be translated to the stock price from pure data garbage. You must pick one, two, no more than three value drivers for your investment case. If you haven’t identified those yet or just have too many of them, maybe you still don’t have an investment case. From previous posts, remember to make them visible and challenge them. Try to disprove your hypothesis and formulate new ones with their respective value drivers.

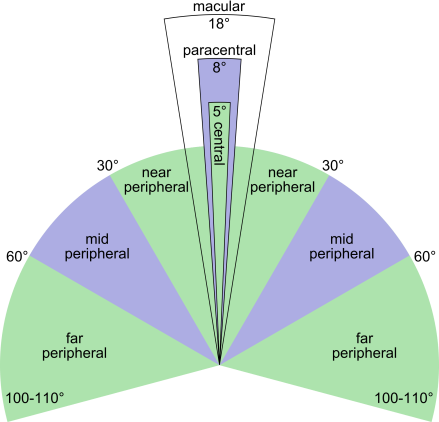

Psychology of Intelligence Analysis Annotated: Peripheral Vision

This is the third of a series of posts that I try to lay down the most relevant lessons from the book Psychology of Intelligence Analysis by Richard Heuer.

I believe this one topic, perspective or better yet, peripheral vision, to be one of the trickiest to analysts. It’s easy to literally get lost as research per se is simply never-ending. “Data collection” pitfall might play a big role in security analysis.

Perspective or Peripheral Vision

- “By studying similar phenomena in many countries, one can generate and evaluate hypotheses concerning root causes that may not even be considered by an analyst who is dealing only with the logic of a single situation.”

- There are many possible market segmentation exercises that possibly yield interesting questions, such as geographic, demographic, social, ethnic, economic, political, etc. The concept of horizontality here is introduced in the business environment analysis. Conclusions are dangerous since causality is difficult to fathom;

- “Historical analysis often precede, rather than follow, a careful analysis of the situation. The most productive use of comparative analysis is to suggest hypotheses and to highlight differences, not to draw conclusions.”

- Verticality: understanding how a specific firm and its sector weathered prior crises and demand peaks are great expectation calibrators. A little history coupled with sector-specific operational know-how satisfy analysis from this particular angle;

- “When faced with an analytical problem, people are either unable or simply do not take the time to identify the full range of potential answers.”

- Combining horizontality & verticality, with a little luck and a sharp mind, you can have a holistic view of the subject company. After spending a good time imagining possible scenarios and their impact in the key value drivers, you are likely set to have a investment-case-oriented research project;

Additionally, mind PR/IR company departments exist for a couple of reasons. One of them is to be the regular communication channel with investors. Also, a crucial part of their job description is storytelling. That’s the story the company tells investors during meetings with investors. Beware if one does not own the framework, one becomes susceptible to whatever story he is told.

The bottom line is extensive sweeping for comparisons propels better questioning, thus enabling one to ask sharper questions and to ponder new possibilities that previously weren’t even considered. To do that, peripheral vision is required.

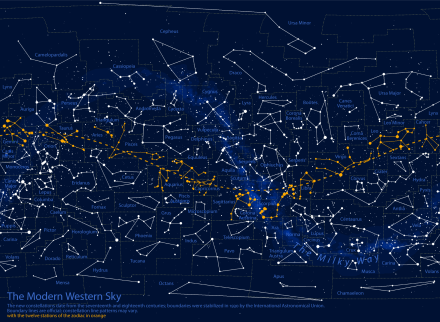

Psychology of Intelligence Analysis Annotated: Making Things Visible

I recently ended up reading Psychology of Intelligence Analysis from Richard Heuer, based on a compilation of declassified articles from the CIA’s Center for the Study of Intelligence, prepared for intelligence analysts and CIA directors. My previous post was about the analyst job in a series of posts that I try to lay down the most relevant lessons from the book.

Moving forward, one must grasp the whole to notice the missing parts. But if the whole isn’t visible, you likely wouldn’t have noticed the constellations drew in the above picture. Once they are noticed, they become obvious. And that’s what I wanted to talk about today.

Making Thinking Visible

- “Intelligence analysts should be self-conscious about their reasoning process.”

- “The analyst operates from a set of assumptions about human nature and what drives people and groups. Those are like to remain implicit in the analysis.”

- “The question is not whether one’s prior assumptions and expectations influence analysis, but only whether these influences are made explicit or remain implicit.”

- “One’s attention tends to focus on what is reported rather than what is NOT reported. It requires a conscious effort to think about what is missing but should be present if a given hypothesis were true.”

- “Assumptions are fine as long as they are made explicit in your analysis and you analyze the sensitivity of your conclusions to those assumptions.”

All of those excerpts from the book points to a single direction, which is the name of the topic I picked: make things visible (explicit). That should be the mantra. Acknowledging it is the first and so important step, but some tools should help the routine.

Writing is a topic I have already discussed here and I consider to be of the utmost importance. Sharing the research material previously with colleagues enriches the discussion and leaves time to other people criticize your thinking. Colleagues should not only read the material for the meeting, but also look up for complementary material that could reinforce or invalidate preconceived hypotheses. The ultimate step would be for the whole company to have a single investment thesis documenting the team’s work on the object company, not the lead analyst’s view on it.

Finally, when reviewing the material, always use two questions to check the rationale behind every assumption: “Is it? If so, why is it?” Those are brilliantly simple questions capable of enabling information sharing among team members and even debunking pseudo robust hypothesis.

I believe there’s much more to develop on this topic, but I believe those are a good first step in a profitable direction.

“Seeing should not always be believing.”

Psychology of Intelligence Analysis Annotated: The Analyst Job

What entertains me the most is learning and the discovery journey. Sometimes you are able to assemble the puzzle, sometimes you have to live with no answers and simply deal with. And that’s why I find the topic of Intelligence Analysis so interesting. I have recently read Psychology of Intelligence Analysis by Richard Heuer, based on a compilation of declassified articles from the CIA’s Center for the Study of Intelligence, prepared for intelligence analysts and CIA directors. I intend to make a series of short posts containing what I deemed to be the most relevant from the book, categorizing topics and commenting to fit my, and hopefully our, needs.

The Analyst Job

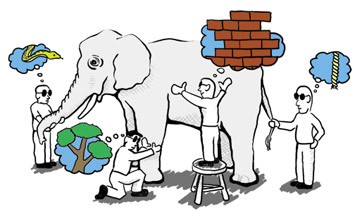

- “Human mind has limitation dealing with ambiguous information, multiple players and fluid circumstances”

- This is what the real world is all about. Acknowledge it and be humble. Consider nonprobable hypotheses. Deconstruct boundaries. Fathom scenarios.

- “We must battle against bureaucratic and ideological biases. The other guy most likely have a different cultural background, life premises and values. People built-in systems are not the same. One must understand people’s values and assumptions, and even their misperceptions and misunderstandings.”

- Remember companies actually are a group of people working towards theoretical global goals and many individual goals. Consider each key member of it and their respective background. Motivations are crucial. Mind those are not explicit most of the time .

- “It always involves an analytical leap, from the known to the uncertain. And still, you are not going to be certain. It’s a matter of odds a sense-making. The intelligence analysts function might be described as transcending the limits of incomplete information through the exercise of analytical judgment”

- Some questions are simpler puzzles, others lead analysts to mysteries. Grasp not even executives know what lay down on the road for their companies. Be skeptical and proceed with caution.

- “When dealing with a new and unfamiliar subject, the uncritical and relatively non-selective accumulation and review of information is an appropriate first step. But this is a process of absorbing information, not analyzing it. Analysis begins when the analyst consciously inserts himself into the process to select, sort and organize information.”

- Usually it’s more interesting begin collecting non-biased information than biased ones (company filings vis a vis sell-side reports). The extensive work of number-crunching, people background checking and reading competitor-related articles are exploratory. One starts creating value when one begins to think, i.e., lays down an opinion on a summary (investment case).

- “Major intelligence failures are usually caused by failures of analysis not collection. Relevant information is discounted, misinterpreted, ignored, rejected or overlooked because it fails to fit a prevailing mental model.”

- We must see the whole to notice the missing parts. Additionally, we must recognize the linchpin pieces of what could be a potential investment. No doubt this is easily said than done. Experience helps a lot here. History also. Shortcuts? Read, read, read…

- “Analysts will often find, to their surprise, that they can construct a quite plausible scenario for an event they had previously thought unlikely.”

- This could be translated as “Hey, please take a step back and think it over.” Second-level thinking helps a lot, i.e. extensive sense-making.

- “When one recognizes the importance of proceeding by eliminating rather than confirming hypotheses, it becomes apparent that any written argument for a certain judgment is incomplete unless it also discusses alternative judgments that were considered and why they were rejected.”

- This trick helps a lot dealing with confirmation bias. Being extensive in your preliminary research aids to eliminate biased thesis ahead. “What if” aids tremendously when fathoming investment cases.

- “What is difficult to find, and is most significant when found, is hard evidence that is clearly inconsistent with a reasonable hypothesis.”

- One can never be so certain.

“The historian uses imagination to construct a coherent story out of fragments of data.” – Richard Heuer

Framing Ever-Changing Business Environments

Analogies between chess and investing are somewhat frequent. What those usually fails to address is that the chess game is a closed-end system (masters usually memorize thousands of game set-ups like an algorithm so they can outplay opponents), while investments analysts and investors are required to constantly assess the ever-changing business environment. Taking a step back, sometimes the definition of what the business environment is not that linear. At the end of the day, it’s like investing is a matter of perspective and framing, not data collection and processing per se.

Additionally, it’s worth emphasizing what Heuer put brilliantly when he addressed the downside of mental models: it’s the principal source of inertia in recognizing and adapting to a changing environment.

There is a crucial difference between the chess master and the master intelligence analyst. Although the chess master faces a different opponent in each match, the environment in which each contest takes place remains stable and unchanging: the permissible moves of the diverse pieces are rigidly determined, and the rules cannot be changed without the master’s knowledge. Once the chess master develops an accurate schema, there is no need to change it. The intelligence analyst, however, must cope with a rapidly changing world. (…) Schemata that were valid yesterday may no longer be functional tomorrow.

Learning new schemata often requires the unlearning of existing ones, and this is exceedingly difficult. It is always easier to learn a new habit than to unlearn an old one. Schemata in long-term memory that are so essential to effective analysis are also the principal source of inertia in recognizing and adapting to a changing environment.

From Psychology of Intelligence Analysis; Richard Heuer